28 Jun The innovator

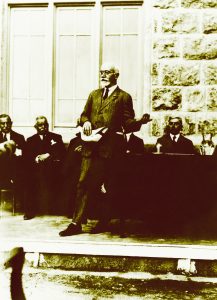

Eleftherios Venizelos had the capability of choosing his collaborators, inspiring them with his vision, and of monitoring personally every creative activity. Thanks to these merits, which had already been manifested during his Cretan days, he became the cherished leader of both the lower and the bourgeois classes and the most appropriate politician to rescue Greece from the political and economic impasse that had come to a head in this country in 1909.

Eleftherios Venizelos had the capability of choosing his collaborators, inspiring them with his vision, and of monitoring personally every creative activity. Thanks to these merits, which had already been manifested during his Cretan days, he became the cherished leader of both the lower and the bourgeois classes and the most appropriate politician to rescue Greece from the political and economic impasse that had come to a head in this country in 1909.

His creative career in Greece started, when he became Prime Minister in October 1910 after elections in which he entered as an independent candidate and was elected first deputy for the constituency of Attica and Boeotia. His policy did not involve a full breach with the past, but focused on the need for modernizing the Greek state and society. He built on the positive results of measures Stephen Dragoumis had introduced during the short but exceedingly creative period of his premiership. Venizelos immediately founded a new ministry, the Ministry of National Economy, which he entrusted to a close friend and political associate of his, Emmanuel Benakis, a businessman and not a professional politician. This Ministry concentrated duties that had been scattered among other ministries until then and related to economic development: trade, communication, industry, agricultural policy and the administration of the financial-credit system.

Under his guidance, the Ministers of his first governments performed remarkable achievement in the domains of economic reconstruction, military reorganization, internal security and labour legislation.

Nevertheless, the wars that broke out during the decade 1912-1922, the social and economic crisis of the inter-war period and the refugee issue interrupted the pacific, creative work of the first three-year period. Under the harsh conditions of World War I, during the period of the Provisional Government of Thessaloniki, Venizelos introduced a series of radical measures in the domains of agricultural and urban-planning legislation: agricultural reform and an urban plan for the reconstruction of Thessaloniki, which had been afflicted by a devastating fire in August 1917. Of course, the political adventures that followed the reunification of the Greek State from 1917 until 1923 did not full implementation of these measures throughout the country.

The inter-war period was one of economic, social and political crisis for the whole of Europe. The Greek economy, which had been stabilized since 1910 and had endured the turmoil of the war, collapsed after 1920. In addition to these troubles, post-war Greece had been saddled with extra burden of rehabilitating 1,500,000 refugees, victims of the Asia Minor disaster, and of carrying out the exchange of populations.

However, despite these unfavourable conditions and his advanced age, the period of Venizelos’s last term as a Prime Minister from 1928 to 1932 was the most creative phase of his political career. The establishment of new institutions, educational and agricultural reform, legislation in the fields of labour and social welfare, a continuation of the legislation inaugurated during the period 1910-1914, the urban-planning and zoning policy and his interventions in issues of economic policy bear the personal mark of his modernising drive.

Ever since the time of World War I Venizelos had removed the economically and socially critical sectors of transport, agriculture and health from the authority of the Ministry of National Economy, creating independent Ministries. In 1929 he founded an independent Air Ministry, which he undertook together with Alexander Zannas, his Deputy Minister. The first national airline, the Société Hellénique de Communications Aériennes (S.H.C.A.), was created in 1931 and operated the lines Athens – Thessaloniki and Athens – Agrinio – Ioannina.

The issue of the right of coinage was resolved in 1928 by the foundation of the Bank of Greece. The institutions of the Supreme Economic Council and of the Council of the State were also founded then.

As far as the sector of agriculture was concerned, the Ministry of Agriculture was founded, training and research in agriculture were promoted, technical projects were undertaken on a larger scale and agricultural credit was strengthened, mainly, by the foundation of the Agricultural Bank of Greece in June 1929.

This four-year period was identified with an extensive educational reform involving, above all, school curricula, school building and the improvement of university education.

The creative work of this last four-year period was interrupted unexpectedly by the consequences of the economic crisis that had broken out in Wall Street in 1929, soon affecting Europe. The reduced Greek budget was unable both to fund planned public projects and to meet the country’s international liabilities (mainly the amortisation of old loans and war debts).